This article is part of #Never_Modern, a series curated by #Hidden_Architecture where we explore the conditions of several #urban_projects from 1950s onwards that, starting from the hypothesis of the #Modern_Movement, they surpassed its #orthodoxy to adapt the #urban_features to #local_conditions.

Este articulo es parte de #Never_Modern (#Nunca_Modernos), una serie comisariada por Hidden Architecture donde exploramos las condiciones de varios #proyectos_urbanos de 1950 en adelante en los que partiendo de las #hipótesis del #Movimiento_Moderno, se superaron la #ortodoxia de varios postulados para adaptar sus #características_urbanas a las #condiciones_locales.

“After the initial works carried out by the constructor, it is thought that the remaining works on the ground floor and on the first floor will be carried out, in their style, by the owners themselves.

“Después de las obras iniciales realizadas por el constructor, se piensa que los trabajos restantes en planta baja y en la planta primera los realicen, a su estilo, los mismos propietarios.

The diagram of the house growth shows, according to self-construction phases, the process of a house for 4 people until completing a house on the ground floor (8 people or more). This is understood as the growth type method. From now on the extension takes place on the first floor, either as an independent dwelling, or, in the case of large families, such as extra bedrooms and living areas, in which case the ground floor could be used for other purposes such as garage, store , stockage …

El diagrama de crecimiento de la casa muestra, según fases de autoconstrucción, el proceso de una vivienda para 4 personas hasta completar una casa en planta baja (8 personas o más). Éste se entiende como el método tipo de crecimiento. De aquí en adelante la ampliación se produce en la planta primera, sea como vivienda independiente, sea, cuando se trate de familias numerosas, como dormitorios adicionales y zonas de estar, en cuyo caso la planta baja podría destinarse a otros fines como garaje, tienda, almacén…

The minimum housing, for 4 people, presents the kitchen, the dining room and the living room all combined. As the house increases in size and is able to accommodate 6 people, the dining room and living room are separated from the kitchen by means of a wall and doors. The wall occupies a new position at the time when the house must accommodate 8 people, getting a bigger living room just as the families also get bigger. (…)

La vivienda mínima, para 4 personas, presenta combinados la cocina el comedor y el estar. Conforme la vivienda aumenta de tamaño y es capaz de albergar a 6 personas, el comedor y el estar se separan de la cocina mediante una pared y puertas. La pared ocupa una posición nueva en el momento en que la vivienda deba albergar a 8 personas, experimentando el salón un crecimiento acorde con el de las familias.(…)

- Author: James Stirling

- Location: Peru (LIma)

- Year: 1969

- Function: Collective Housing

- Elements: Patio

- Status: Built

- Tags: Conglomerate Ordering, Courtyard, Flexibility, Neo-Modern Urbanism, Time, Urbanism

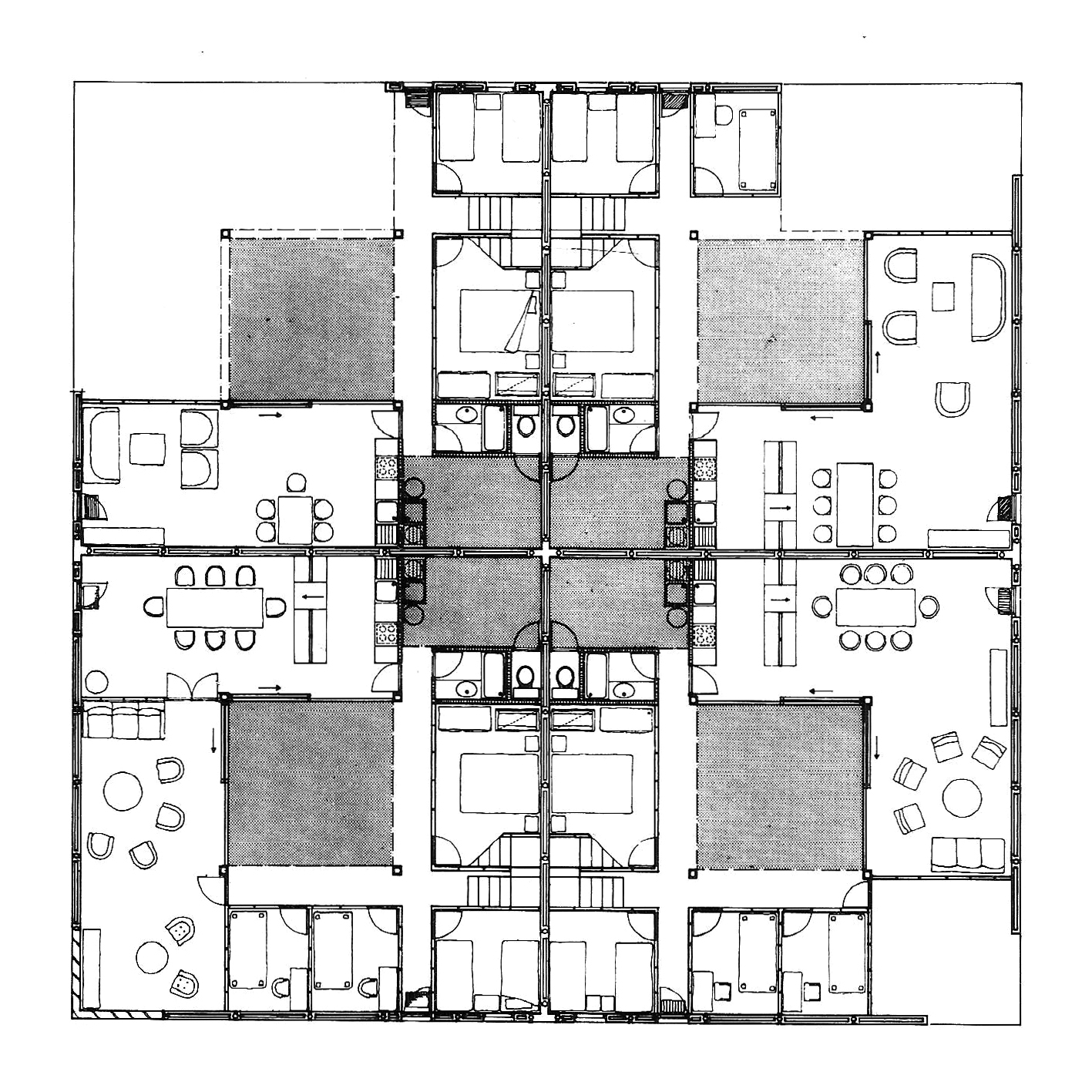

(…)All the houses have two main entrances on the front, one directly to the living area (social / traditional), another (functional) in the circulation area, leading to the staircase and the garden courtyard, through the service.

(…)Todas las viviendas poseen dos entradas principales en la fachada anterior, una directa a la zona de estar (social/tradicional), otra (funcional) en la zona de circulación, abocada a la escalera y al patio ajardinado, a través del servicio.

The initial works assigned to the builder benefit from large-scale production (cost and speed of execution); they consist of housing units that are assembled based on prefabricated concrete walls and slabs. The party walls and exterior walls are of sandwich type, precast, leaning on beams supported by the land. They are also equipped with the relevant openings for doors and windows.

Las obras iniciales asignadas al constructor se benefician de la producción a gran escala (coste y velocidad de ejecución); consisten en unidades de vivienda que se montan a base de muros y forjados prefabricados de hormigón. Las paredes medianeras y exteriores son de tipo sandwich, prefabricadas, que descansan en jácenas apoyadas en el terreno. Van dotadas además de las pertinentes aperturas para puertas y ventanas.

As the rooms are clustered around the landscaped courtyard, also groups of houses of various sizes are associated in community and social spaces of different categories. The hierarchy is developed from the personal house to the neighboring houses, forming an initial cluster of four around the common party walls that surround the service patios. In turn, the groupings of four houses congregate around a common entrance courtyard, so that they make up another higher order composed of 20 or 21 houses. “

James Stirling

A semejanza de como las habitaciones se arraciman en torno al patio ajardinado, también las agrupaciones de casas de varios tamaños se asocian en espacios comunitarios y sociales de diversa categoría. La jerarquía se desarrolla desde la casa personal hasta las casas vecinas, configurando una agrupación inicial de cuatro en torno a las paredes medianeras comunes que rodean los patios de servicio. A su vez, las agrupaciones de cuatro casas se congregan alrededor de un patio de entrada común, de modo que componen otra de orden superior compuesta por 20 ó 21 casas.”

James Stirling

In each of the different human societies throughout history, at least for a large part of it, housing is conceived as a living organism that evolves at the same time as the community, family or not, evolves. blanket. It will be already with the birth of what we know as modern societies, under the umbrella of a liberal economy that prioritizes the value of change over the value of use, when there is a notable fracture between housing and human being. The needs to which housing typologies will begin to respond will be different from those that were regulated according to the biological sense of the communities.

En cada una de las distintas sociedades humanas a lo largo de la historia, al menos durante gran parte de ella, la vivienda se concibe como un organismo vivo que evoluciona al mismo tiempo que lo hace la comunidad, familia o no, que en ella se cobija. Será ya con el nacimiento de lo que conocemos como sociedades modernas, bajo el paraguas de una economía liberal que termina primando el valor de cambio por encima del valor de uso, cuando se produzca una notable fractura entre vivienda y ser humano. Las necesidades a las que comenzarán a responder las tipologías habitacionales serán otras bien distintas de aquellas que se regulaban en función del reloj biológico de las comunidades.

From the first cabin rediscovered by Laugier, or its complementary space dug from earth, to popular models that still survive supported by a vernacular culture in underdeveloped societies and always placed outside the market, the domestic space has incorporated in some way time as a factor of project and reason for being. When housing is conceived as a totally enclosed and finished space, denying any possibility of reconfiguration or growth in the future, it denies to itself the first cause of its existence: to serve as an organic shelter for a social structure that is so.

Desde la primera cabaña que redescubriese Laugier, o su complementario espacio excavado en la tierra, hasta modelos populares que aún perviven apoyados sobre una cultura vernácula en sociedades poco desarrolladas y colocadas siempre al margen de los mercados, el espacio doméstico ha incorporado de alguna u otra manera el tiempo como factor de proyecto y razón de ser. Cuando la vivienda se concibe como un espacio totalmente acotado y terminado, negando toda posibilidad de reconfiguración o crecimiento en el futuro, niega a sí mismo la causa primera de su existencia: servir de cobijo orgánico a una estructura social que también lo es.

The houses that the market offers in advanced societies are already finished products even before knowing, as if they could know, the tenants that will lodge. The possibilities that they offer do not respond in any case to the needs that their future inhabitants could have. Its spatial or structural characteristics come from market studies of economic profitability, but rarely from others of sociological origin. Thus, the inhabitants of a house grow, add or subtract individuals over time, their characteristics and physical, environmental or psychological needs mutate within a space that does not have the ability to be modified easily, to accommodate unforeseen situations necessarily happenning throughout the course of a life.

Las viviendas que el mercado ofrece en las sociedades avanzadas son productos ya terminados incluso antes de conocer, como si pudieran conocer, a los inquilinos que alojarán. Las posibilidades que ofrecen no responden en ningún caso a las necesidades que sus futuros habitantes podrían llegar a tener. Sus características espaciales o estructurales proceden de estudios de mercado de rentabilidad económica, pero rara vez de otros de origen sociológico. Así, los habitantes de una vivienda crecen, se suman o restan individuos con el paso del tiempo, sus características y necesidades físicas, ambientales o psicológicas mutan dentro de un espacio que no tiene la capacidad de ser modificado con facilidad, de alojar situaciones imprevistas que necesariamente acontecen a lo largo del transcurso de una vida.

Due to its precariousness and its external position regarding the flows of the market, the informal world of the most disadvantaged social classes is denied the possibility of access to “decent” housing. Based on the need and the almost total lack of resources or tools, housing models of a minimum material quality are developed in this context, in most cases, but with a spatial and evolutionary potential much greater than those of any another housing model belonging to the system. These small constructions present an organic behavior, grow and develop according to the needs and possibilities of their inhabitants, starting from minimal cells that become more complex as the family unit also does it. In this context, housing continues to be an organic being capable of being synchronized with the needs of the community that inhabits it.

Por su precariedad y su posición externa respecto a los flujos del mercado, el mundo informal de las clases sociales más desfavorecidas ve negado la posibilidad de acceso a una vivienda “digna”. A partir de la necesidad y la ausencia casi total de recursos o herramientas, se desarrollan en este contexto unos modelos habitacionales de una calidad material ínfima, en la mayoría de los casos, pero de un potencial espacial y evolutivo mucho mayor que los que tiene cualquier otro modelo de vivienda perteneciente al sistema. Estas pequeñas construcciones presentan un comportamiento orgánico, crecen y se desarrollan en función de las necesidades y posibilidades de sus habitantes, partiendo de células mínimas que se complejizan a medida que la unidad familiar también lo hace. En este contexto, la vivienda continúa siendo un ser orgánico capaz de ser sincronizado con las necesidades de la comunidad que lo habita.

The humble neighborhoods of Lima outskirts, like so many other cities, have developed from their origins in this context of informality and precariousness. The competition organized in the 60s, PREVI, aimed to respond to a need for housing with a minimum of material quality resolved with minimal resources. The novelty, its structural vocation from the beginning to incorporate time as a project element in the development of the neighborhood and housing. Thus, flexibility, versatility or mutation capacity are transferred from the informal to the academic or professional world, guaranteeing a qualified architectural response.

Los barrios humildes de la periferia de Lima, como de tantas otras ciudades, se han desarrollado desde sus orígenes en este contexto de informalidad y precariedad. El concurso convocado en los años 60, PREVI, pretendía dar respuesta a una necesidad de vivienda con un mínimo de calidad material resuelta con recursos mínimos. La novedad, su vocación estructural desde el inicio de incorporar el tiempo como elemento de proyecto en el desarrollo del barrio y las viviendas. Así, la flexibilidad, polivalencia o capacidad de mutación se transfieren desde el mundo informal al académico o profesional, garantizando a priori una respuesta arquitectónica de calidad.

In spite of currently presenting a hardly recognizable aspect, the houses that James Stirling executed in the PREVI neighborhood are probably the ones that solved in a more successful way the problem of guaranteeing flexibility and mutability over time. James Stirling was very clear that his proposal should be only a beginning, a base, which would be completely hidden by multiple layers and diluted in its appearance, but not in its presence. Although the houses would be developed according to the possibilities, and also tastes, of the inhabitants, the minimum cell proposed by Stirling had to remain and govern the subsequent growth. This somewhat infrastructural character, as Stan Allen would define decades later, of the domestic space is the fudamental success of the proposal of the english architect. Prior to the presentation of the proposals, James Stirling looked carefully and studied some informal neighborhoods in Lima. The main conclusion drawn from this analysis was that the uncontrolled growth of housing caused domestic and urban spaces of zero quality, totally inadequate for the proper development of a community. What could be considered from the beginning as a positive quality, flexibility over time, became the cause of all evils if it developed without control. Surely the greatest success of the approach of the PREVI competition was to generate a dialogue between this informal world of great potential but no resources and the academic sphere, with sufficient tools but approaches to housing problems too canonical or dictated by models that the market itself defines.

A pesar de presentar en la actualidad un aspecto difícilmente reconocible, las viviendas que James Stirling ejecutó en el barrio de PREVI son probablemente las que resolvían de una manera más exitosa el problema de garantizar la flexibilidad y mutabilidad a lo largo del tiempo. James Stirling tenía muy claro que su propuesta debía ser sólo un inicio, una base, que quedaría totalmente oculta por múltiples capas y diluida en su aspecto, pero no en su presencia. A pesar de que las viviendas se desarrollasen según las posibilidades, y también gustos, de los habitantes, la célula mínima propuesta por Stirling debía permanecer y regir el crecimiento posterior. Este carácter de alguna manera infraestructural, como definiría décadas después Stan Allen, del espacio doméstico es el éxito fudamental de la propuesta del arquitecto inglés. Previamente a la presentación de las propuestas, James Stirling se fijó detenidamente y estudió algunos barrios informales de Lima. La principal conclusión que extrajo de este análisis fue que el crecimiento incontrolado de las viviendas provocaba espacios domésticos y urbanos de nula calidad, totalmente inadecuados para el correcto desarrollo de una comunidad. Lo que podría ser considerado desde un inicio como una cualidad positiva, la flexibilidad en el tiempo, se convertía en el causante de todos los males si se desarrollaba sin control. Seguramente el mayor acierto del planteamiento del concurso de PREVI fue el de generar un dialogo entre este mundo informal de gran potencial pero ninguna herramienta y la esfera académica, con herramientas suficientes pero unas aproximaciones a la problemática de la vivienda demasiado canónicas o dictadas por los modelos que el propio mercado definía.

How does James Stirling manage to guarantee a capacity for growth and change over time without negatively affecting the environmental quality of the home? The answer was not found, of course, too far. The typology of courtyard housing is present since the beginning of humanity. The understanding of this typology from an “infrastructural” approach allowed James Stirling to redefine what had always occurred in vernacular architecture: the main courtyard, defined a priori by the structure of the dwelling itself, is the catalyst and controller of the buildings progressive growths. Provided that the patio is never occupied, different rooms can appear as new cells on a single level or, once one is fulfilled, make the house grow in height. Each of the interior rooms enjoy in this circumstance natural lighting and cross ventilation.

¿Cómo consigue, James Stirling, garantizar una capacidad de crecimiento y mutación a lo largo del tiempo sin que esto repercuta negativamente en la calidad ambiental de la vivienda? La respuesta no la encontró, desde luego, demasiado lejos. La tipología de vivienda patio está presente desde los inicios de la humanidad. El entendimiento de esta tipología desde una aproximación “infraestructural” permitió a James Stirling a redefinir lo que en la arquitectura vernácula se había producido siempre: el patio principal, definido a priori por la propia estructura de la vivienda, es el catalizador y controlador de los progresivos crecimientos. A condición de que el patio nunca sea ocupado, distintas estancias pueden aparecer como nuevas células en un solo nivel o, una vez colmatado uno, hacer crecer la vivienda en altura. Cada una de las estancias interiores disfrutan así en toda circunstancia de iluminación natural y ventilación cruzada.

The key to the success of James Stirling’s proposal was undoubtedly to place the patio in a central position in each of the plots, making the prefabricated concrete structure that would support the successive growths define the emptiness itself as the heart of the living place. Thus, the horizontal structure will always be placed from the perimeter of the patio to the outer perimeter of the plot, guaranteeing that the central chore always conserves its organizing essence. Linking the community space of the house, the patio, with an infrastructural understanding of the domestic typology facilitated a growth always from the order, from a strongly defined base in an initial state. As the community appropriated these spaces and these housing units, the aesthetic appearance of the dwellings, especially the facades, changed completely. However, the ability of the patio to regulate growth has allowed all to retain their spatial structure despite having exhausted growth in height. This special feature has provided a great versatility of use to these structures, having been for example reconverted one of them in a small school.

La clave del exito de la propuesta de James Stirling fue sin duda colocar el patio en una posición central de cada una de las parcelas, haciendo que la estructura prefabricada de hormigón que soportaría los sucesivos crecimientos fuese la que definiese el propio vacío como corazón de la vivienda. Así, la estructura horizontal se colocará siempre desde el perímetro del patio al perímetro exterior de la parcela, garantizando que el vacío central conserve siempre su esencia organizadora. Vincular el espacio comunitario de la vivienda, el patio, con un entendimiento infraestructural de la tipología doméstica facilitaba un crecimiento siempre desde el orden, desde una base fuertemente definida en un estado inicial. A medida que la comunidad se fue apropiando de estos espacios y estas unidades habitacionales, la apariencia estética de la viviendas, especialmente de las fachadas, cambió por completo. Sin embargo, la capacidad del patio de regular el crecimiento ha permitid que todas conserven su estructura espacial a pesar de haber agotado el crecimiento en altura. Esta característica tan especial ha dotado de una gran polivalencia de uso a estas estructuras, habiendo sido por ejemplo reconvertida una de ellas en un pequeño colegio.

Unfortunately, experiments such as PREVI had a very limited scope and no impact beyond the academic world. The rules of purchase-sale of the market with often speculative aim do not leave space for a typological innovation that returns the organic and human nature to the domestic space.

Lamentablemente, experimentos como el de PREVI tuvieron un alcance muy limitado y una nula repercusión más allá del mundo académico. Las reglas de compra-venta del mercado con fin muchas veces especulativo no dejan espacio para una innovación tipológica que devuelva el carácter orgánico y humano al espacio doméstico.

Google Street photos

About

Hidden Architecture was created in February 2015 between Madrid and Liverpool by Alberto Martínez García and Héctor Rivera Bajo.

Hidden Architecture fue lanzado en Febrero de 2015 entre Madrid y Liverpool por Alberto Martínez García y Héctor Rivera Bajo.

ISSN 2530-8904

EDITORS

Alberto Martínez García (Madrid, Spain. 1988)

Architect from the Higher Technical School of Architecture of Madrid (ETSAM) and Master of Architecture II post-professional degree from The Cooper Union (New York). Currently living and working in New York, I have previously worked and lived in Shanghai, Amsterdam, Portugal, England, and Madrid. My interests include the importance of history in contemporary architecture, the evolution of housing, and the expression of contemporary culture on a small scale such as interior and product design.

More info

Héctor Rivera Bajo (Ciudad Real, Spain. 1987)

Architect from Higher Technical School of Architecture of Alcalá (ETSAUAH). After some years of studying and working at Lisboa and Madrid, I am currently settled down in Zürich. My interests are focused on the use of certain spatial patterns within the domesticity realm to trace Territorial Hierarchies and produce identity by social and community space. This approach to the Infrastructural Nature of Architecture must be considered from a critical attitude in regard to architectural historiography.

FORMER COLLABORATORS

Biljana Janjušević

Marta López García

Ángela Parra Sánchez–Moliní

Matthew Bellomy

Alexandrina Marinova

Germán Andrés Chacón

* * *

If you want to contact Hidden Architecture Team, feel free to write us to

editors@hiddenarchitecture.net for any comment, idea or suggestion.

Whenever possible, we try to attribute images, drawings, and quotes to their creators and original sources. Please write us if you notice misattributions or wish something to be edited or removed.

Website developed by Pedro López Andradas

Ha

Laisser un commentaire